The Leadership Year: Month Five

It’s taken us 5 months to tackle this… but Time Management was always going to be an area of focus on the Leadership Year. Whether we think we’re good at time management or see areas for improvement there’s always a big incentive to find ways of managing our time better. In the history of work, there have never been more challenges to managing our time. We work longer hours than ever before. Technology makes it easier for work to interrupt leisure time and real time communication pushes us to be able to do more and more. Alongside these factors, we are more aware of the need for a good work/life balance and finding approaches to wellbeing that see us feeling fulfilled by our work rather than stressed.

There are so many time management techniques out there. If you asked a group of people what their top tips were they’d all suggest different things they’ve done that have been gamechangers for them. And actually, when it comes to time management this is a great place to start. Whilst I spend a lot of time looking at theorists in my role, actually sometimes the small practical tips can really pay dividends with time management. Turning off the email pop up notification to minimise distractions is one example. Setting times where you are on DND so as to focus is another. They are small, simple steps but for a lot of people they work.

And at the heart of time management, we should continue to look at what works for us, then convert good practice into long term habits. But where do we start with finding what will work? I want to share 3 time management theories with you, as 3 different things to try. Some may work for you, some won’t, but if we can try new approaches, we will continue to create better habits and feel more confident about how we manage our time.

The Pomodoro technique is a great one to start with. Named after the Italian theorist’s tomato shaped kitchen timer, Pomodoro’s are blocks of time that we use to be able to create more focus. They work in 3 simple steps:

1. Decide what you are able to do in the next 25minutes

2. Set a timer, and work solidly for 25 minutes minimising all distractions

3. When the timer sounds, stop exactly where you are, and spend 5 minutes reviewing progress and deciding the focus for the next 25 minutes

Then repeat!

For independent work this can be really beneficial. I worked with lots of people in the early days of lockdown who found this particularly useful for adapting to solo work. I like the technique as it can help focus the mind. A big task that will take hours is unlikely to see me concentrating throughout, but if I tell myself I only have to focus for 25 minutes then I am far more likely to give a task my full attention. It can also be helpful in terms of improving my time predictions. When I first started using the Pomodoro technique, I found it really hard to gauge how much work I could get done in 25 minutes, but over time I found I was much better able to estimate time, which helped me collaborate better with others in my business as when working on shared tasks I could quickly see how long something would take. It’s also helpful to have the 5-minute review time. Sometimes I might find my work has gone off on a tangent! The review time allows me the time to take stock and decide if I want to continue or switch tasks.

But I do think it can be a bit limiting for some people. Having a 5-minute review every 25 minutes feels a bit excessive to me. So, I find myself adapting this technique. I look at what task I want to do then decide how long to work on it. It’s never more than 45 minutes at a time (as otherwise I feel it’s hard to avoid the distractions) but I might set a timer for just 10 minutes for some tasks. I still use the time after the timer has sounded to stop and review. Do I want to forge ahead? Or would I be better making progress on something else? When I have a lot of work to get through, I can sometimes use this approach to make steady progress in multiple areas rather than working on getting tasks complete one at a time. This leads me nicely onto the next technique!

Bluma Zeigarnik is one of the lesser-known time management theorists, but I have found her technique to be really impactful both personally and when I tutor others. Bluma was an educational pioneer for women in the early 1900s. She highly valued her education and spent hours in the library reading. This led her on the path to studying memory where she discovered one of the most effective tools to combat procrastination I have come across.

The Zeigarnik effect is really very simple indeed. “We are more motivated to complete tasks we have already started”. It is a very easy concept to remember, but behind the theory is solid science that is a little more complicated. Our brains are actually hardwired to try and complete tasks. With every completed task we get a burst of dopamine, a chemical that makes us feel good. It’s a good feeling when we can cross something off our to do-list and so our brain craves its next ‘fix’ of dopamine as quickly as possible. As our brain seeks the quickest possible path to get dopamine, it always starts with tasks we’ve already started. Hence why we feel more motivated to complete these tasks. It can also be described as ‘closing loops’. Our brains don’t like untidy incomplete tasks, so we feel more driven to get them finished and ‘close the loop’. So as basic and obvious as it sounds, the best way to complete a task is to get it started in the first place!

But be prepared to embrace the awkwardness of a partially completed task. An essay left mid-sentence. A presentation with just a title page. An e-mail half-typed and saved into drafts. Often when faced with a task it feels too big and daunting and we procrastinate until we absolutely have to get it done. But if we could start even the biggest of tasks with some small steps like these, our brains will do the hard work of motivating us to completion. The more we can break down these tasks into small steps (& they can be shockingly small!) the more frequently we’ll get little bursts of dopamine and be able to feel the momentum to our time management. For self-motivation and discipline this is a great technique to use!

But what happens when you have more than yourself to think about? As leaders we may need to not only ensure we are good at time management but that everyone in our team can also work to the same tine goals. I believe it is absolutely critical to ensure everyone on the team has the same understanding of priorities as you do, and this can be achieved by using the principles of Steven Covey’s matrix (also known as the Eisenhower matrix).

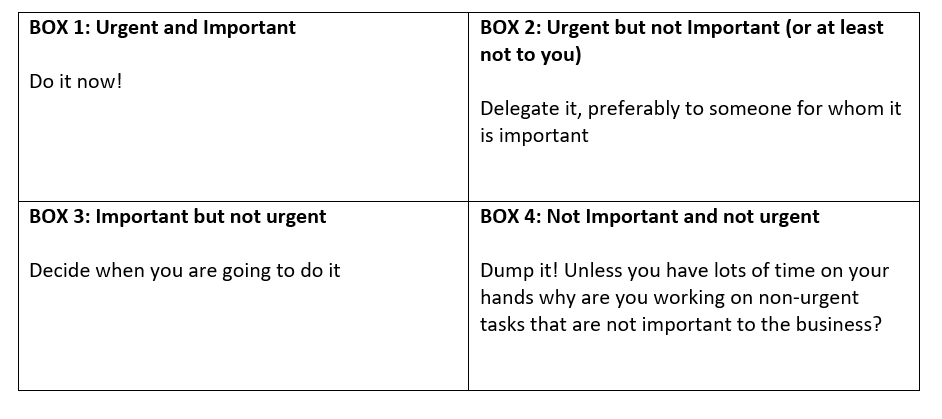

Covey suggests there are 2 factors to take into consideration when managing tasks. How important they are, and how urgent they are. Often in real life practice the urgency can take over the importance. My background in a commercial environment is a classic example of that. There may be an urgency to a task due to a superficial deadline, IE a cut off point for revenue reporting. This can lead decisions to be made based on ‘who shouts the loudest’ rather than what is the most important outcome for the business. Whilst booking and reporting revenue is of course important, should this be at the expense of generating additional revenue? From a business perspective a temporary delay in order processing is preferable to losing out on earning potential. Whilst one task may be perceived as urgent, actually the other may be more important.

Covey presents this as a matrix to aid decision making:

The issue with this matrix is that on its own it isn’t enough to change a team’s understanding of urgencies and priorities (or levels of importance). Without a thorough understanding of the business an individual may still make a different judgement call on what is urgent and what is important. As Leaders, we need to use our experience to share how we make decisions to create a universal understanding of what is urgent and important. In the commercial example I gave, the decision as to what was more important directly related to revenue potential. If I share my decision-making rationale as often as possible with the team, they will know that revenue potential is an important metric. Decisions in business are often more complicated than this, but the more leaders share the thinking behind their decision, the better able a team are to reach a level where they all share an understanding of what is truly urgent and important.

I also share this matrix with my teams. Most individuals will describe their working weeks as busy. When presented with new tasks, we’ll often push back saying we already have a lot on. But if teams can communicate to each other using the boxes in their communication, a leader can better establish how busy the team truly are. If a team of individuals are all working on box 1 tasks and feel unable to hit their deadlines, then you know you have a time management emergency on your hands. Your team are at capacity and contingencies will need to be explored. However, this is actually quite rare. What is more common is that everyone is busy, but some of the team are working on box 1 tasks and others on boxes 2 or 3 (or in some cases even box 4). By creating a shared understanding of what tasks fall into which boxes, this allows an agile approach to time management – flighting in those individuals working on box 2 or 3 tasks to ensure the box 1 tasks, which are truly the most urgent and important, to be covered where necessary. Naturally this also means shared processes and structures need to underpin working practices, but the matrix minimises issues for leaders who run busy teams.

There are countless other time management theories and ideas out there. Spending just a few minutes exploring them can really pay dividends in the long run, but if you’re going to explore the above here are some tips to get you started:

1. Try and include 1 Pomodoro practice a week into your schedule. Once you get used to it, increase the frequency and experiment with different timings until you find what works for you

2. Start something and deliberately leave it unfinished! Reassure yourself that you will come back to in the future, but pay attention to how the Zeigarnik effect motivates you to finish the tasks

3. Allocate some typical team tasks into the 4 boxes of Covey’s grid and consider how you would explain your decision making to your team